Manchester United’s Wayne Rooney (L) scores their second goal during the English Premier League match between Crystal Palace and Manchester United at Selhurst Park.

Manchester United – and David Moyes – haven’t exactly had a fruitful season. They lie in sixth place after 27 games – level on points with Everton in seventh, who have a game in hand. They were knocked out of the FA Cup at the first hurdle, in front their own fans. They displayed the fighting spirit of the bygone Fergie era to score in the last minute of their Capital One Cup semifinal, only to surrender meekly in the penalty shootout, a dismal act witnessed again by the Old Trafford faithful.

They face Olympiakos in the knockout stages of the Champions League this week; a tie they will be expected to win. But, should they get through, it would not be remiss to claim that the bookies’ odds would be stacked heavily against them when they come up against any of the European powerhouses in the quarter-finals.

Amid all the losses of this season, Wayne Rooney‘s revival represents David Moyes’s only victory. The fact that Rooney has put pen to paper on a new deal worth £300,000/week, when United fans were resigned to losing him in the summer, is an unexpected silver lining. Given Rooney’s revelation in October 2013 that his midfield role was behind his desire to leave, one can assume that this month’s contract talks would have included assurances on his striking role in the future. And Moyes would do well to follow through.

Rooney’s selflessness at putting the team above all else has at times seen him pushed to the wing, or dropped into midfield to make up the numbers. The fact that he felt that he “had to be a bit selfish” is a kick in the face of United supporters, particularly since it does away with one of the major factors which made him a firm fan favorite at Old Trafford.

Notwithstanding the player’s displeasure, efforts could be made to convince him to play in midfield, were his talents better utilized in that position. There is an argument, that in the absence of a creative box-to-box player, Rooney could add Scholes-like vision and passing to United’s midfield. He could also add, dare I say it, Scholes-like tackling.

But Wayne Rooney – the midfielder, I believe, is the quintessential example of the 80-20 rule. 80% of his impact comes from 20% of his play. He plays the brilliant cross field Hollywood passes, the through balls over the top and makes the odd lung bursting run to put in a last ditch block. But in his desire to play the expansive decisive passes, he often takes too long on the ball and ultimately slows the game down. In fact, his passing accuracy sometimes even drops when he goes into midfield.

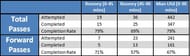

Comparison of Rooney’s passing statistics in the first and second halves with the team average. Stoke City vs. Manchester United, Britannia Stadium, Stoke, February 01, 2014. (Statistics compiled using FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Case in point – United’s loss against Stoke at the Britannia a couple of weeks ago. Danny Welbeck came on just before half time as a replacement for the injured Phil Jones and partnered Robin van Persie up top for the duration of the second half. For Rooney, this meant dropping into midfield alongside Tom Cleverley.

There exists evidence to suggest that Rooney’s performance dropped in the second half.

His pass completion rate, a metric which is usually highest for midfielders, went down from 79% to 69%. When we look at only forward passes played, it suffered a far more drastic drop from 71% to 57%. This is suggestive of Rooney’s tendency to try to force a forward pass where none exists.

Wayne Rooney – forward passes – 2nd half.Stoke City vs. Manchester United, Britannia Stadium, Stoke, February 01, 2014.(Courtesy: FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Rooney is brilliant, when as a trequartista, he drops into the midfield zone in search of the ball and orchestrates play. Not so much, when he plays as part of a two man midfield. As the former, he gets to be the spare man, the man who receives the ball in a pocket of unmarked space and uses the time subsequently conjured to magic up a moment of genius. As the latter, he doesn’t always receive the ball in these spaces and is thus not as effective.

It is interesting to see that his passing map, in terms of the areas he operates in, is rather unaffected by his role. Even as a striker, Rooney regularly provides the creativity from deeper areas which United seem to lack. And this is a responsibility he takes on naturally in addition to goal scoring duties. He doesn’t need to play in midfield to be a driving and creative force from that area of the park. He does it anyway. In fact, he is better at it when he plays as the second striker.

Wayne Rooney – passes (2nd half) – as a midfielder against Stoke.Stoke City vs. Manchester United, Britannia Stadium, Stoke, February 01, 2014.(Courtesy: FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Wayne Rooney – passes – as the second striker against Crystal Palace.Crystal Palace vs. Manchester United, Selhurst Park, London, February 22, 2014.(Courtesy: FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Additionally, when in midfield, it is common to see Rooney being dispossessed of the ball as a result of dwelling on it for too long. Since he often gets shifted deeper when United are chasing, this makes United susceptible to counter attacks. It is only a matter of time until one such counter results in a goal.

Some might still argue that the potential benefits of Rooney’s passing and chance creating abilities are too great and playing him in midfield is a viable strategy, especially when United are behind and need to bring on Welbeck or Javier Hernandez. But that would mean ignoring the strongest aspect of Rooney’s game – his finishing.

With 209 goals in 429 appearances, Rooney sits at 4th in the all time scoring charts for Manchester United. He is 28, the age at which players usually peak. This is the time to make full use of Rooney – the goalscorer. The time for Rooney – the midfielder will come. Playing in midfield will help in prolonging his career when his legs can no longer keep up. The transition will be a natural one for a player of Rooney’s ability and temperament, but it is a transition which should still be a ways off.

It is only natural that a shift into midfield would limit a player’s chances of scoring. Rooney played a total of 70 minutes in midfield against Fulham and Stoke, and all his shots were either blocked or from outside the box; the only one on target was a free kick which Stoke’s Asmir Begovic tipped onto the bar.

Wayne Rooney – shots – 2nd half.Stoke City vs. Manchester United, Britannia Stadium, Stoke, February 01, 2014.(Courtesy: FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Wayne Rooney – shots – (69-90+) mins.Manchester United vs. Fulham, Old Trafford, Manchester, February 09, 2014.(Courtesy: FourFourTwo Stats Zone)

Rooney and van Persie can be the most devastating strike pairing in football, but it is lagging behind the Suarez-Sturridge and Aguero-Negredo partnerships in the Premier League itself. It is time Moyes utilized the potential of this pairing to its full extent rather than entertaining thoughts of playing a world class striker in midfield.