In each edition of Gimmick Some Lovin', we take a look at one iteration of a gimmick match available on the WWE Network. Some are iconic for their success, others for the extent to which they flopped, and some just... happened.

We defined a "gimmick match" as, in any way, adding a rule/stipulation to or removing a rule from a match, changing the physical environment of a match, changing the conditions which define a "win", or in any way moving past the simple requirement of two men/women/teams whose contest must end via a single pinfall, submission, count out, or disqualification.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017, the WWE presented Smackdown Live from Manchester, England, although the "Live" part of that title wasn't exactly the case for viewers in the United States. Many of those US viewers were a little less than pleased that the company decided to promote a spoiler on all of its official social media platforms (as well as push notifications on its official app) that a "major title change" had occurred in the UK (which turned out to be AJ Styles regaining the WWE Championship from Jinder Mahal, the only title bout announced in advance for the show).

10 WWE Stars Who Are Now Banned - Find Out Now!

Today, we'll take a look back at another time the company's top prize changed hands on a show that didn't air 100% live, with the results spoiled for fans before the change occurred. This time, however, it was rival promotion World Championship Wrestling doing the spoiling of the finish to Mankind vs. The Rock in a No Disqualification Match in the main event of the January 4, 1999 edition of Monday Night Raw.

According to preliminary ratings, Tuesday's spoiler might have had the same effect as the spoiler for this match almost 19 years ago, as Smackdown rebounded with its largest television audience in nearly two months (and one of its ten best of 2017).

A Deadly Game

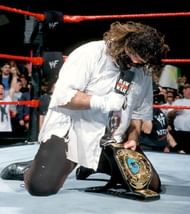

Mick Foley, in his persona as Mankind, had spent the summer and fall of 1998 trying his hardest to please and impress Vince McMahon and his faction, The Corporation. Foley used everything in his arsenal, including clowns, viciously attacking Corporation foes, balloons, chair shots, cake, getting absolutely annihilated in violent contests against multiple opponents, dressing in ratty dress shirts and ties, and even sock puppets to try to please his boss. McMahon, for his part, did make Foley a singles champion for the first time, with Mankind becoming the first ever Hardcore Champion.

When a "Deadly Game" tournament was announced for the 1998 Survivor Series to crown a new holder of the vacant World Wrestling Federation Championship (the belt having been vacated due to Steve Austin's nagging injuries and/or massive storyline contrivances), the implication was that McMahon was grooming the Hardcore Legend for his first WWF Championship.

The other performer with the most storyline focus heading into the tournament was The Rock, who had slowly been building a babyface turn through the summer of 1998 as his expressions, moveset, and, especially, catchphrases began catching on with audiences nationwide, and boos gradually dissolved into cheers. The face turn was official as September wore into October, and the Corporation entered Deadly Game vowing two things:

- The group would do everything in its power to keep The People's Champion away from the belt.

- There would be a repeat of the previous year's main event controversy.

In an instant double turn for both men, the second of those predictions came true in the finals of the tournament as The Rock placed Foley a weak and sloppy-looking Sharpshooter, with McMahon immediately ordering for the bell to be rung, in an exact duplicate of the improvised finish to the previous year's Survivor Series title bout in Montreal. Mankind had been rejected by his Corporate pals, and The Rock was the new face of the company.

If the show had ended there, it would have been a classic shocker ending but, in a repeat of the era when "Hogan must pose" to close out every show, Austin interrupted Rock's title celebration to basically delegitimize the new champ and lay waste to the Corporation.

While Austin had to fight to regain his right to challenge for the title he never lost, Rock moved into his first feud as the titleholder against the man who has screwed out of the belt: Mankind.

Meanwhile, on the other channel

For anyone born or taking up wrestling fandom after 2001, there's a fact of life for grappling fans in the mid-to-late 1990s that's crucial to this story: very few fans actually turned on either the USA Network for Raw or TNT for Nitro and left their television on that network for the entire show. Commercial breaks, boring promo segments, and Buff Bagwell matches were all subject to the previous channel (or whatever your particular remote had to instantly switch between two networks) button to see what was happening on the competitor's show.

WCW knew this would be the case before premiering Nitro in the fall of 1995, and actually relied on a wrestling audience already seeing Monday as the day for spandex and singlets. Their main strategy to disable the PREVIOUS CHANNEL button, and to keep the Nielsen Ratings for themselves, was to rely on Vince McMahon's money-saving tactic of recording multiple episodes of Raw at the same taping and airing the episodes at a later date.

If Eric Bischoff could get someone in the WWF's arena to make note of what happened on those pre-taped shows, he would have the commentary team (or, often, Bischoff himself) casually announce the results of "the other show" to prevent anyone from clicking over out of curiosity.

In the case of the above Intercontinental Championship contest, for instance, Bischoff remarked from the Nitro commentary desk, “Hey and by the way, in case you’re tempted to grab the remote control and check out the competition, don’t bother, it’s 2 or 3 weeks old. Shawn Michaels beats the big guy with a superkick you couldn’t earn a green belt with at a local YMCA. Stay right here, it’s live it’s where the action is.”

January 4, 1999

Eight days prior to this night, on December 27, 1998, World Championship Wrestling had done the unthinkable: it ended the undefeated streak (and first World Championship reign) of Bill Goldberg at Starrcade when Scott Hall used a cattle prod to help Kevin Nash overcome the former NFL tackler.

Knowing that the McMahons would be airing a pre-taped Raw on January 4, WCW sought to maximize their live advantage by promoting what would have, two years prior, been a dream contest: the now-estranged founders of the New World Order clashing as Nash was slated to defend his new title against Hollywood Hulk Hogan.

In the World Wrestling Federation, meanwhile, The Rock was successful in his first pay-per-view title defense against Mankind at December's Rock Bottom event; Foley's fan support continued to rise as The Rock's win required significant interference by Corporation members Shane McMahon, Gerald Brisco, Pat Patterson, Ken Shamrock, and The Big Bossman (one of these things is not like the other).

Mankind's frustration came to a head on the Raw slated to air on January 4, as he held Shane McMahon in an amateur wrestling hold (taught to Foley by his high school coach) until McMahon the Elder agreed to put The Rock's championship on the line in the show's main event.

The Rules

The match is a No Disqualification Match, so the match can only end via pinfall or submission in the ring. In the storyline, this was done to ensure that the Corporation could not be punished for aiding their champion, but in reality, it seemed like a way to unlock the door to maximum chaos and silliness.

Putting Butts in Seats

If you have cable or satellite television service, go ahead and try to set your DVR to record WCW Monday Nitro. Notice something off?

There are a lot of reasons why you can't do that right now, and January 4, 1999, is one of the biggest. Dozens of weeks of WCW dominance over Monday night basic cable ratings began to erode in the spring and summer of 1998, with D-Generation X riding a tank and singlehandedly saving the wrestling industry as we know it gaining steam as off-color babyfaces and crowds nearly blowing the roof off arenas across America when the glass shattered at the start of Austin's entrance theme.

WCW, meanwhile, proved that innovation was still its MO, and gave fans such never-before-seen main events as Hogan vs. Randy Savage, Lex Luger vs. Savage, and Hogan vs. The [Legally Unable to be Ultimate] Warrior, not to mention never-before-wanted PPV clashes like Diamond Dallas Page and Jay Leno vs. Hogan and Bischoff or Page and NBA star Karl Malone vs. Hogan and Dennis Rodman (there seems to be a pattern here, but I can't quite put my finger on it).

What was once a weekly slam dunk for Atlanta became a weekly toss-up, and by the dawn of 1999, the World Wrestling Federation was winning more often than losing.

Desperate to "move the needle", Bischoff tried the one-two punch of WCW tricks to pop a big rating: giving away a marquee title change on free television and spoiling the WWF's pre-taped programming to disable remotes nationwide.

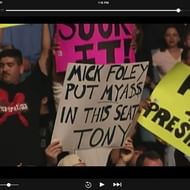

Multiple times throughout the broadcast, Bischoff had announcer Tony Schiavone make the comment that Mick Foley, formerly Cactus Jack in WCW, would be winning the World Wrestling Federation Championship, a move which he caustically noted: "will put a lot of butts in seats."

Ninety-nine times out of 100, spoiling a major main event in that way would have kept viewers away from the competing show, but this was no ordinary spoiler. Schiavone promised viewers that, if they changed the channel, they would see a grizzled veteran win his first singles championship in the World Wrestling Federation in a cathartic victory over the evil heels who had been tormenting Federation babyfaces for months (while Schiavone's own show would be presenting an old man with mobility issues and poor cardio taking on an even older man with more mobility issues and worse cardio).

Literally, hundreds of thousands of fans (nearly two-thirds of a million) changed the channel and did not change back, after the first announcement, and subsequent announcements (including the start of the main event slot) had similar effects on WCW's dwindling audience. Often, rating graphs for the two shows at the time showed corresponding peaks and valleys depending on what was being presented head-to-head; Raw's ratings were mostly growing peaks as the night wore on.

The Match

From the entrances alone, we know that this one is going to be insane. Foley, perhaps to counter the Corporation's influence (and perhaps just so that Russo can work as many characters into one booking as possible) comes out with all of D-Generation X as his entourage (and with his old "Ode to Freud" music, which would not long after this match be replaced by the car wreck and guitar riff).

As wrestling matches go, the action is pretty basic Attitude Era brawl. Acknowledging the no-DQ aspect of the match allows some freedom with that style, as it finally makes sense that the performers spend an inordinate amount of time on the outside of the ring. Rock makes some brutal hits with the steel ring steps, and I'm distracted by how odd it is to see Test holding on to the championship belt for Rock.

As basic as the action is, so many things make it work: The Rock's intermittently joining commentary (a Rock staple at the time, which Foley mocks excellently later on), Vince's pleased smirks with Shane, Foley choking the life out of Rock at the announce table, and some of the stiffest 2017-WWE-would-never-allow-this weapon shots you can find.

By the time Rock puts Foley through the announce table with a Rock Bottom, the Worcester, MA, crowd is lit, and I can remember at the time (and on subsequent rewatches) thinking that Schiavone's spoilers were an error, because the match was playing out like any other Corporation bait-and-switch from Raw outings at the time.

Going from good to great, Rock mocks Mr. Socko with a final taunt added to the People's Elbow, and the crowd pushes the decibel meter even further after a Mankind kick-out.

This match does so much with so little; each successive Foley kick-out and hope spot gets thunderous applause, and the action is so basic that it's great character work getting the cheers. I remember once seeing a critique of WWF written around this time that Papi Chulo could hit a triple moonsault off a cage and it wouldn't get a tenth of the applause a Steve Austin punch could, and nowhere is that emphasis on the characters (not the moves) more evident than in this match.

In writing about the "pills match" we took Russo to task for not caring enough about the in-ring product to put on a good wrestling show, as opposed to a good television show, but this is one of those areas where it works.

The match's climax sees a pier-six brawl erupt between D-X and the Corporation, and as the crowd simmers in the enjoyment of 3-4 smaller fights taking place all over ringside, the familiar glass shatters, and at least 15,000 people probably develop permanent hearing damage because that place explodes, then only gets louder when Austin nails Rock with the chair and places Mankind on top of him for the three count.

Austin disappears again and leaves Foley to celebrate, and Vince and Shane to hyperventilate. Worcester is alive like few crowds have ever been, partly out of the joy of seeing such a respected performer become "The Man", partly out of the catharsis of Vince and company finally getting their due, and partly out of the disbelief of what they had just seen. It's the pinnacle of what Russo's shock-first-explain-later style could accomplish.

However, the reason this match succeeds and Bischoff's spoilers failed is because of the characters, not because of the shock of the finish. It's particularly telling that nearly a million people turned on Raw knowing exactly how it would end (and, probably, because they knew how it would end). The how and the why of the finish mattered, and the exultant pop that Foley received (duplicated in living rooms nationwide) is proof positive.

One need only look at the Twitter commentary after Tuesday's Smackdown Live, which most fans knew the ending too long before it aired: the joy of seeing Mick Foley or AJ Styles take the big one wasn't going to be deterred by knowing it was going to happen. If anything, it amplified the hope spots when both men's nights looked darkest.

My Rating

If I were to watch this match on mute with no knowledge of its context, my rating would be a firm 2/10, not much more than a standard television match from this period.

However, as an artefact of professional wrestling, and as a demonstration of effective character work making a storyline, as opposed to the story's shock value, this match is perfection. It's everything the "sport" is supposed to be: drama, emotion, tension, and an "oh my god!" release when the underdog finally wins the big one.

WWE, throughout much of its territory, was a "babyface territory," where the booking was focused on a good guy champion attempting to retain his championship against a murderer's row of monstrous challengers (i.e. Hogan's 1984-1993 run).

In this time period, the company began experimenting more with an NWA-influenced "heel territory" booking, because the territory really did belong to the business's biggest heel: McMahon himself. Like Flair taking the popularity of men like Dusty, Sting, and Steamboat into the stratosphere years earlier, the Mr. McMahon persona gives this match and Foley's win a Midas touch like no other.

Credit this to Vince Russo's storytelling all you want, but it's really the payoff of tremendous investment in character by a much more important Vince.

Again, as a wrestling match, I'd go 2/10, but as professional wrestling, I'd go the full monty and give this 10/10.

Meltzer Says:

I can't, for the life of me, find Meltzer's ratings for this one, but it's safe to say he found it more palatable than WCW's one-move "Fingerpoke of Doom" that aired simultaneously, wherein Hogan poked Nash in the chest for the three-count, the NWO reunion, and the WCW Championship (and all the subsequent mediocrity it garnered).

Make Sportskeeda your preferred choice for WWE content by clicking here: Source preferences